History/Tarih P.1

Village history part 1.

The origins of Lurucina date back to possibly the 12-13 century AD. Lurucinali’s have a unique and diverse background that makes them feel special. The ability to converse in Turkish, Greek and English was, and still is a source of pride. One thing is certain, no matter what part of the world they have settled in, the people of our village have shown themselves to be adaptable, entrepreneurial and determined to succeed, and yet the love and yearning for their village is greater than ever.

The unity of the family groups gave a strength of belonging, and the often ridicule of our unique local culture by other Cypriots cemented the bond to a level that was rare even by Cypriot standards.

The aim is to refresh and urge all generations to learn of our past & carry it to future generations. The last fifty years has seen an exodus that has decimated this unique and beautiful village’s population to less than when the British took over in 1878. Politics, poverty and modern travel have all played a part. One thing is certain the vast majority of us regardless of their now home, UK, USA, Australia, Turkiye, Canada or any other part of the world will always have their heart beating in the valley of Lorenzia.

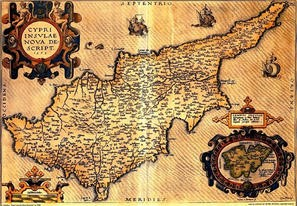

According to the maps of the Venetian period Lurucina was named Lorthing. In the 1540s however it was registered as Lorichina in the Contrada di Visconta (District of Visconta) which seems to indicate a Lusignan origin possibly 12-13 centuries AD.

The Venetian census from the early 1500s may indicate that most of the inhabitants were Orthodox Greeks and a small number of Latins. The surrounding villages like Damalia, Aya Zorzi, Aya Marina and Malloura had some Latin communities.

The most detailed record of these villages was for Malloura. The records for 1565 recorded 81 adult freedmen (Francomates may have been freedmen, but legally they were still servants of their Latin Lords), an estimated population of 196 women and children (1).

Malloura’s origins date to the Roman period with an estimated population then of between 188-258. It was abandoned during the Arab-Byzantine period but re-settled during the Frankish Lusignan period. It was a thriving village and the people earned their living from cereals, vineyards, orchards and herding .[2]

Athienou was the first farming village in the valley. It was established in the 1st century BC when Cyprus became a Roman Province. To the north of Lurucina however is the oldest town of the area which is the Ancient Idalion, founded in the early period of Greek settlement over 3000 years ago.

The Venetian census of 1562 established that there were 246 villages belonging to the state and 567 belonging to the nobility and Church. [3] The peasant’s were simply tenants and owned no land.

A short explanation would help explain the feudal system in Cyprus during Venetian rule. The class difference played an important role in how the Island was ruled.

The Paroiki/Parici and the Perperiarii classes in particular were downtrodden. The Paroiki (Parici) had to perform 2 days slave labour for the state and their Lords as part of their taxation. In addition they had to hand over anything between 20-66% of the crop they produced on their meagre land even though the land belonged to their Lords, who had absolute jurisdiction over the Paroiki (Parici). They were treated as mere slaves and suffer any punishment short of mutilation and death.

The Perperiarii had risen from the Parici and had become ”freemen”. Their name derived from the tax which they paid in gold coins called ”hyperpers”. Most of the civil servants and wealthy citizens of Nicosia were from the Perperiarii, this of course did not save them from the wrath of the ruling Venetian lords who looked down on both classes.

The Lefteri (eleutheroi) were also called Francomati. This class came mostly from the Parici made a substantial payment to their lord, but still had to carry on paying 10-20% of their crops to the lord for setting them free. In addition they had to pay tribute to the King in return for privileges. Though nominally free they were still subject to the jurisdiction of the ordinary magistrates .[4]

The Cypriot population during the Venetian period like the Ottoman period showed some wild fluctuations during the 82 years of occupation. A quick glance at the following table is enough to show this fluctuation.

| (Parici. landless Serfs). | Francomati (Freed slaves). | Total | |

| End of the 15th century Parici | 47,185 | 77,066 | 124,251 |

| 1540 (F. Attar, M.L. III, 534) | 70,050 | 95,000 | 165,050 |

| 1562 ( B Sagredo, M.L. III,541) | 83,653 | 47,503 | 131,156. [5] |

As can be seen from the statistics, while the fortunes of the peasant class changed wildly, the actual population hardly increased in 82 years. Gilles Grivaud the French researcher also quoting from the book, has all helped our knowledge on the local history surrounding Lurucina.

Their information gives us some informative details of the villages and populations around Lurucina in the last years of Venetian rule. The details below are from the 1562 or 1565 records.

the few villages mentioned.

Malloura 81

Athienou / Atirne 61

S Zorzi (Petrofan ? ) 1

Damidia / Damalia) 31

Lympia 88

Louroujina / Lorthina 186

Potamia 66

Dhali 158. [6]

Important note; The figures above may or may not include women and children. As can be seen in the first paragraph, Malloura may have had 81 ”Freedmen” but the estimated population was 196. If that was to apply to Lurucina than the estimated population would be in excess of 300-350. It’s unlikely however. In the absence of concrete archive evidence this is only speculative.

It’s clear from the historic records that Lurucina was a larger village for the period. The population was even larger than Athienou/Kiraci Koy and Dhali/Dali. The Ottoman census of 1572 of 24 households is not so detailed on the head count. A reasonable guess could be around 100-130 inhabitants. It does seem however that a drop in the population took place. If so, no doubt this would be the Latin element, and would explain why some families were transferred during the siege of Famagusta .[7] and of course some Ottoman settlers after the war. As many Latin homes were abandoned many of their homes were offered to new settlers or the soldiers who fought to capture the island.

Perhaps the most far reaching reform was the fact that the land or properties the peasants owned was that they were allowed to keep the land they owned on a perpetual lease basis with the right to pass the inheritance to their children.

The Cizye for non Muslims divided the status of the religions. An advantage for non Muslims was that they were not obligated to do national service with the result that they carried out their business and trade at a higher level than the Muslims who were often sent abroad to die and had less time to improve their family farms.

Some non Muslims did not like this and some conversions to Islam were undertaken. This was mostly among the remaining Latin’s who found themselves facing the backlash from their Orthodox neighbors and their new Ottoman masters.

Conversion was a way of saving their lives and provided some security in their daily lives. After a few years the persecution declined in some areas and like Athienou village the Latin’s were allowed to practice their faith, but were only permitted to work as hired muleteers. To this day Turkish Cypriots call Athienou by the name of ‘Kiraci koy’, which simply means the hirers or tenants.

One of the most interesting records which gives us an opportunity to make some comparisons with the village under the Venetians is the first tax valuation carried out on Lurucina ( Named Lorthina at the time ) by the Ottomans in 1572. This is because of Halil Inalcik’s research in 1969 of his Ottoman policy and administration in Cyprus after the conquest. [8]

The following information is on page 21 table 2.

Population

Households 24 Adult males 27

Batchelors 3 Total tax 810

Widows 0

Tithes

Wheat 900

Barley 1,050

Flax –

Cotton –

Fruits 975

Olives 55

Two

Beehives 10

Cocoons –

Garden produce –

Sheep-tax 20

Pig-tax 40

Fines & other dues 95

From properties without heirs etc 75

Rural guardianship –

Mills –

Tavern

Total; 4,030.

The Jizye (Military exemption tax) for Lurucina was about 26-27% of the total tax paid by the Christians in the first Ottoman census. The burden of having to work at least 2 days a week for their Venetian Lords was reduced to one day; this must have been a great relief for the people of Lurucina as the extra day gave them the opportunity to concentrate on their own crops. Another advantage soon became apparent, as the landless peasants were allowed to keep the land they worked on a ”perpetual lease,” with the right to pass on their holdings to their sons, this in effect turned the peasants into land owners. Title deed registrations did not come into effect however until the mid 1800s. A sworn testimony by at least 2 witnesses and the local Imam or priest was sufficient to prove ownership of land.

Lurucina’s tax liability for 1572. [9].

Jizye Total of all taxes percentage of tax average tax burden

collected in kind per adult male

1,620 5,704 54 210

Judging from the above taxpayers population we can come to a rough estimate that the women were in equal numbers and perhaps half the population may have been children. Some disabled, or old men were of course exempt. With Turkish settlers still not in large numbers a fair guess for 1572 would be that the people were predominantly Christian. By 1643 the tax census showed that 41 households were Christian. [10] At the time of editing this information the figures for the Muslim population has not been found. All we can say is that the ” Iskan defteri” ( Settlement Book ) Republic of Turkey Prime ministerial Archives , Kamil Kepeci Defter ( Book ) No 2551, listed Lurucina as having received some settlers in 1572. More details on this are given further down on this page.

Once the conquest of the island by the Ottomans was over the tax system was overhauled, which helped ease the burden of taxation. The list below gives some idea of the relief to the poorer classes in particular .[11]

Venetian Period Ottoman period

2 days forced labour One day a week forced labour

60,80 or 90 akche 30 akche from each tax as ispenje tax

Taken as fixed taxes

5 akche per head as salt tax Abolished

60 akche for each mule born Abolished

25 akche for each cow Abolished

Giving birth

1 akche for each sheep yearly Abolished

1 akche for each lamb Abolished

One third share of the crop

In the vineyards Abolished

One and a half akche for

Every donum of land Abolished

25 akche for each mare born Abolished

Not applicable A new tax of 60, 80, 100 akche according to the family’s wealth, was introduced for non Muslims. This was called the Cizye. (this tax made the Christians exempt from national service)

The situation in Cyprus before the Ottoman conquest was one of total domination and persecution by the Latin Venetians against the majority of Orthodox Christians who were predominantly Greek speaking.

The entry of the Ottomans gave control to the Orthodox Church. This move was the death knell for the Latin community. Many either fled the island, were massacred or converted to Islam in order to avoid persecution.

Was Lurucina Latin, Orthodox, or were settlers brought in from Turkey? There is no conclusive answer as the absence of written archive information makes it difficult to know with any precision.

The question would be to ask if the fable of Lorenzia has any foundations in fact.

In the book “Names and locations of Cyprus lost in the depths of 2500 years of history” by Dr Ata Atun the name starts with Lorthing then changes to Looretzena onto Louroujina and now Akincilar. [12]

The Latin community, although smaller than the Orthodox Greeks owned large tracts of land around Ay Sozomenoz, Bodamya and Lorthina (Lurucina) Aya Marina was in fact a Latin Church. In 1643 there were 13 households registered in the village of Aya Marina. After a devastating earthquake in August of 1735 the surviving inhabitants moved to the village of Limbya which was originally called Olympia, no doubt the numbers of Latin’s were much less then the Orthodox population, and in time many converted to either Islam or Christianity

According to M de Cesnola who went to Cyprus during Ottoman rule the vast majority of “Linobambaki” were originally Latin’s, who converted to save their lives, but secretly practiced the Christian faith. [14] Some historians among them Sir Harry Luke,and Rupert Gunnis concluded this to be the result.

What they did not mention however is that from the mid 1700s to early 1800s a new wave of Turkish families came to the village which completely changed the ethnic makeup of the village. [15] The census evidence of the period confirms that the vast majority of today’s genetic roots date not to the 16th century but to this particular migration.

There were of course other Churches in the area. Aya Philidhitiosa near the old Larnaca Nicosia road is one. And let’s not forget that in-spite of a smaller population the Greek Churches of Ay Andronicos (built in 1831) , Panayia and Ay Epiphanios were until the 1950s very active. St Epiphanios went through some restoration in 1864 which seemed to have spoiled the interior. One unanswered question remains on the Byzantine Church of St Catherine which according to R. Gunnis was close to the main Larnaca road 2 miles from the village. [16] In 1935 it was still standing and yet many elders from Lurucina have no knowledge of its existence.

Strangely many maps of the area do not include St. Catherine. There was of course an Ay Katerina in Bodamya, but how could an historian with the calibre of Rupert Gunnis mistake one for the other, if at all, and most important of all he clearly states that the Church 2 miles from Lurucina. In fact the location Gunnis describes sounds very much like the location of Aya Marina. The Mosque itself is not as old as most Churches, the existing mosque was built in the late 1800s or early parts of the 1900s, but the minaret was added in the 1930s. The central position of the mosque may give us a clue that some families may have settled in the early parts of Ottoman rule.

The Tahura family ( Ismail Ali ‘Gicco’ for example) who owned the properties adjacent to the mosque allegedly only came to the village from Turkey around the late 1700s to early parts of the 1800s. The question is who owned the land prior to the purchase by Mustafa Sari Tahura?

The 1882 maps of Lord Kitchener prepared soon after the British took over Cyprus in 1878 does in fact show that the mosque was in existence. It may not be the same building, but a smaller building that was used as a mosque. [17] More research needs to be done to establish this.

Ancestors of the Galaba’s, Pekri’s, Lao’s, Mavri’s and Kavaz were settled in the area between the Mosque, the small stream that ran through the village and the old Turkish Cemetery. This may suggest older inhabitants of Lurucina.

The Mehmet Katri family tree has been established as being one of the oldest and certainly largest family trees of Lurucina. The Ottoman translations from the 1878 census have confirmed this.

The Arabic Siliono’s who came in the late 1700s settled on the suburbs of the village, this in itself can give us some clue which families may have settled in our village in chronological order. But another strange thing is that the vast majority of the family trees recorded go back 9/10 generations.

No doubt the smaller Greek community lived in the village long before the arrival of the Turks, there is some record on this site of those families, but not much on the enigmatic and elusive Latin community which is reputed to have founded the village.

As the Greek population of Lurucina has been added to our records, it confirms that they were in much smaller numbers, or at least from the mid 1700s on-wards. The Christian population in the 1643 census which registered 41 households prove that at that time the Greek population was larger than in the 1831 census [18] It would be a good guess that many either left the island due to pestilence, drought and malaria that hit Cyprus hard in the mid 1700s [19] some may have moved to the nearest village Limbya/Olympia.

This paved the way for newcomers, namely our families. Aya Marina who registered 13 households in 1643 was also abandoned soon after due to the same reasons and possibly an earthquake which reduced the village to rubble. Most of the inhabitants also moved to Limbya

The Mevkufat Defter written in 1572, records a total 0f 1689 families being transferred to Cyprus from various parts of Anatolia. [20] The question is, who were they and where were they settled?

There are some elders who have suspicions that some of our people were originally Maronite’s, and point to the Church of Aya Marina as evidence. I think we can safely dismiss that assumption on the basis that in August of 1596 and March of 1597 ( only 24-25 years after the Ottoman conquest) Girolamo Dandini, S.J., Professor of Theology at Perugia in Italy went to Cyprus. His mission was to investigate the condition of the Maronite community in Lebanon. but the report he left us on the Maronites of Cyprus included the names of 19 settlements and makes no mention of Lurucina at all. Hagia Marina is however listed. [21]

The following section is from a book by Guita G Huorani and a few other writers including Palmieri. The section that is of most interest is the sections referring to the conversions in Lurucina in the year 1636. The claim by Palmieri in 1905 [22] seems to contradict the report by Jerome Dandini when he visited Cyprus in 1596 and named all the remaining 19 Maronite villages on the Island which does not include Lurucina.

If we can discover the missing period before the 10/11 generations of families recorded on this site then perhaps we can complete the history of ALL THE FAMILIES OF Lurucina. In the meantime our search continues.

BY GUITA G HOURANI

The Cypriot Maronites under Ottoman Domination (1571-1878)

”Known in general as dhimmis or infidels, like other Christians, the Maronite’s were also called Suryani under the Ottomans (Jennings 1993: 132, 148-149). The Ottoman domination of Cyprus brought on the demise of the Maronite colony on the island. As their villages became depopulated through death, enslavement and migration, the Maronite population became almost extinct and, because of persecution and taxation, their bishops and archbishops became non-resident.

While the Greeks did nothing during the Ottoman invasion, the Cypriot Maronites stood beside the Latins in their defense and saw the invasion of the island ruin their settlements. Soon after total Ottoman control over the island, the Ottomans recalled the allegiance of the Maronites to the Latin’s. Similarly, the Greeks remembered the oppression of the Catholic’s, and since most of the Catholic’s who had stayed on the island were Maronites, it was they who suffered retaliation. Together, the Ottoman’s and the Greek Orthodox inflicted the worst treatment on ‘this unfortunate community’ (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462; Cirilli 1898: 14-15). In 1572 the Maronite’s had 33 villages and their Bishop resided in the Monastery of Dali in the district of Carpasie (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462) .

During Ottoman rule, 14 Cypriot Maronite villages became extinct. By 1596, about 25 years after the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus, the total number of Maronite villages had been reduced to 19 (ibid. 1905: col. 2462, Dib 1971: 177). The Ottomans, after annexing Cyprus, imposed increasingly high taxation on the Maronite’s, accused them of treason, ravaged their harvests and abducted their wives and children into slavery (Cirilli 1898: 20). Many Maronite’s had died during the defence of the island, many more were either massacred or taken as slaves, many others dispersed throughout the island to escape persecution, and those who remained in their villages found themselves in a pitiable condition (Cirilli 1898: 14-15). Consequently, a group fled to Lebanon, another group accompanied the Venetian’s to Malta (Dib 1971: 177) and those who stayed behind “had to submit, in addition to the yoke of the conqueror, to that of the Greeks, which was no less troublesome” (ibid. 1971: 177). This treatment was the main reason why appointed Maronite clergy to Cyprus no longer resided on the island and preferred to stay in Lebanon. These atrocities were the most direct cause of the reduction in the Cypriot Maronite population and subsequently in the number of their villages. During this period, the Bishops who served the Maronite’s were Bishop Youssef (+1588) and Bishop Youhanna (1588-1596) (Daleel 1980: 108). While the Ottomans ruled, the Greeks, who had gained a bit of advantage for a while, began their retaliation against the Catholics –– which meant the Maronite’s, who were the only Catholics left on the island (Palmieri 1905: col. 2464). The vengeance of the Greeks began with the confiscation of the Maronite churches and was magnified by their accusation that the Maronite clergy was working for the return of Venetian rule to Cyprus and was plotting against the Ottoman Empire before the Sublime Porte in Istanbul. Consequently, the Ottomans inflicted their anger on the Maronites. They killed, exiled, imprisoned and enslaved many. They obliged many others to embrace the Greek Orthodox rite and to obey the Greek hierarchy. This persecution caused a considerable number of Christian’s, including a good number of Maronite’s, to adopt Islam as a survival mechanism (Cirilli 1898: 11, 21; Palmieri 1905: col. 2468).

By 1636, the situation had become intolerable and the conversions to Islam began. “Since not everyone could stand the pressures of the new situation, those unable to resist converted to Islam and became Crypto-Christian’s, mostly Armenians, Maronites and Albanians in the northern mountain range and along the north coast, particularly at Tellyria, Kambyli, Ayia Marina Skillouras, Platani and Kornokepos” (Jennings 1993: 367). The Maronites who adopted Islam were centred in Louroujina in the District of Nicosia and were called Linobambaci — a composite Greek word that means men of linen and cotton (Palmieri 1905: col. 2468). However, these Maronite who had converted in despair did not fully denounce their Christian faith. They kept some beliefs and rituals, hoping to denounce their ‘conversion’ when the Ottomans left. For example, they baptized and confirmed their children according to Christian tradition, but administered circumcision in conformity with Islamic practices. They also gave their children two names, one Christian and one Muslim (Hackett 1901: 535; Palmieri 1905: cols. 2464, 2468).

Father Célestin de Nunzio de Casalnuovo, a Franciscan from the Holy Land, worked for 33 years on returning the Linobambaci to their Christian religion. Some communities responded and asked him to establish schools in their villages. He obliged by opening two schools. But the Greek hierarchy continued to agitate the Muslim fanatics, who began attacking the Linobambaci and their agriculture fields. The Linobambaci, fearing for themselves, withdrew their religious aspirations and the whole re-conversion operation was halted (Palmieri 1905: col. 2468)”.

The following from Excerpta Cypria seems to contradict Palmieri’s claim above that Lurucina had a Maronite community. As stated earlier Reverend Jérôme Dandini traveled to Cyprus to assess the condition of the Maronite community. Sir Francis George Hill who may have written one of the most comprehensive history of Cyprus claimed that ”Palmieri is almost certainly wrong in deriving them (the Linobambaki) from the Catholic Maronites. [23]

”Reverend Jérôme Dandini, the Envoy of Pope Clement VII, visited the Maronite’s of the island during his papal mission to the Maronites of Lebanon in 1596. Dandini stated the following.

”The Cypriot Maronites were all under the authority of the Maronite Patriarch whose See was in Lebanon. He also declared that at times there was at least one priest for each parish and that sometimes there were eight, like in Metoschi. He named the 19 Maronite villages left in Cyprus: Metoschi, Fludi, Santa Marina, Asomatos, Gambili, Karpasia, Kormakitis, Trimitia, Casapisani, Vono, Cibo, Ieri, Crusicida, Cesalauriso, Sotto Kruscida, Attalu, Cleipirio, Piscopia, Gastria. However, when he visited Cyprus in 1596, he learned that there were not many Maronite clergy left, that many Maronite’s had either fled or apostatized and that there were only ten parishes, the most important being Saint Marina, Cormakiti and Asomatos. He found the Maronites in a miserable situation (Dandini 1656: 23). Noting the poverty of the Maronite people, the lack of priests to serve their communities and the sad state of their parishes, Dandini recommended that the Maronite Patriarch send a bishop to serve the Maronites of Cyprus. In 1598, Father Moïse Anaisi of Akura was designated bishop and he stayed until 1614. He was followed by Girgis Maroun al Hidnani (1614-1634), who was a visiting bishop residing in Lebanon; Elias al Hidnani, who visited the Island at the request of the Patriarch in 1652”. [24]

In the Mevkufat Defter written in 1572, it lists a total 0f 1689 families being transferred to Cyprus from various parts of Anatolia. The policy of settlement increased and gathered pace. In his excellent research listed below, Mustafa Hasim Altan lists a total 5720 families

According to the research done by Mustafa Hasim Altan, an expert in Ottoman writing and a book published in 4 volumes in the TRNC in 2001, he translated the order given by Sultan Selim from the original archives documents at the Republic of Turkey Prime Ministerial State Archives ; Istanbul Ottoman Archives ; Muhimme Defteri ( Muhimme Book) XIX , Page 334-335 . Copy of which is also at TRNC National Archive ; Ref : 728-2531 , Box No 28.

Further information of settlements are sourced from ” Iskan defteri” ( Settlement Book ) Republic of Turkey Prime ministerial Archives , Kamil Kepeci Defter ( Book ) No 2551.

With the arrival of Ottoman’s on the island a great exodus occurred among the Venetian’s. In the preliminary searches it was discovered that 76 villages in the areas of Mesaoria and Mazoto alone were completely abandoned. Hence it became vital that these villages and areas had to be repopulated. Sultan Selim the 2nd’s decree on 21 September 1572 ordered that one out of ten families of the areas selected to be transferred and settled in Cyprus have to be looked at in this light. [25]

Some of the main areas that Turkish people were transferred from were

Iceli, Taseli, Manavgat, Mut, Alanya, Silindi, Burhanlar, Avsar, Maras, Mugla, Cankir, Divrigi, Kayseri, Corum, Tarsus, Bolu, Bursa, Karaman, Bozok, Ulukisla, Akdag, Bor, Ilgin, Shakil, Aksehir, Nigde, Beysehir, Urgu, Develihisar, Kochisar, Seydisehir, Aksaray, Silifke. 5720 families from the regions of central Turkey were eventually transferred.

On arrival some were placed into the villages vacated by Venetians. Some of those villages included Lurijina ( Akyndzhilar) Ay Sozomeno (Arpalyk) , Aytotoro (Bozdağ) , Kalohoryo (Chamlyköy) , Elye ( Doğancı ) , Kocchina (Erenkoy) , Tremetusha (Uzun Mese ) , Aybifan (Esenda) , Amadyez (Günedyez) (Gun) Diabodame (Ikidere), Trahona (Kizilbash-Gelibolu), Xerovuono (Kurutepe), Margi (Kuchukkoy), Vroisha (Yağmuralan), Limniti (Yeshilyrmak), Šillura, Yilmazkoy, Fota (Dağeri, Piğleri) Trapeza (Teknecik) ,Templos ((Zeytinlik) , Prastyo ( Baf -Yuval) , Artemis ( Ardam), Aisimyo (Avtepe), Ovgoroz (Ergazi), Ayharida ( Ergenekon) , Konetra ( Gonendere ), Sinde ( Inönü ), Kritya ( Kutulus ) ( Kutulus ), Avila ( Köliv ), Av Korovya (Kuruova), Livatya (Sazlıköy), Ipsillat (Sutlüce), Evretu (Dereboyu), Melandra (Beşiktepe), Istinjo (Kushluca), Ayastad (Zeybekköy), Klavia (Alanichi), Aplanda, Pergama (Beyarmudue), Petröfünde (Köfünde) (Gechitkale), Mennoya (Otuken), Pile, Goshshi (Three Martyrs), Dzhelya (Lightning), Pitargu (Akkargy), Aksilu (Aksu), Ayyani (Aydin), Anatyu (Gormeli), Antrolik (Gundogdu), Pelatusa (-Karagya, Kavagi) (Kavagi). [26]

It must be noted that not all the families transferred from Turkey were Muslim’s , although vast majority were Muslim , some were Christian’s. After the initial settlements , some Christian’s were allowed to return to the villages that they had vacated . Apart from the villages mentioned above there were villages that were either set up by the soldiers that had taken part in the conquest , or came to settle from Turkey. Just to mention a few as this is outside the scope of this site, Mara, Lefke , Gaziveren , Beyköy, Ortaköy , Airda , Mora , Gönyeli , Marata (Muratağa), Sandallar etc.

As is commonly known some Christian’s had converted to Islam during the Ottoman time for various reasons. How many if any had converted in Lurucina is something we may never know. Though the evidence points to some number of Turkish being transferred to our village just after 1572. In addition a few Latin families that had converted to Islam were also transferred to Lurucina during the siege of Famagusta in 1571. The possibility that there were some other conversions from Christianity may have taken place and should not be ruled out. It seems clear however that most of today’s family trees date from the above mentioned second wave of migrants during the 1700s. There are of course some families that have yet to be identified by their place of origin. In the meantime our search continues.

[1] The Great Map by Leonida Attar. Written by Francesca Cavazzana Romanelli and Gilles Grivaud. Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation. 2006.

[2] The Archeology of Past and Present in the Malloura Valley”, edited by Derek Counts, F. Nick Kardulias and Michael Toumazou, 2012.

[3] Halil Inalcik. Ottoman Politics and Administration in Cyprus after the Conquest. 1969 page 10.

[4] Halil Inalcik. Ottoman Politics and Administration in Cyprus after the Conquest. 1969 page 17.

[5] Halil Inalcik. Ottoman Politics and Administration in Cyprus after the Conquest. 1969 page 15.

[6] The Archaeology of Past and Present in the Malloura Valley, edited by Derek Counts, P. Nick Kardulias and Michael Toumazou, 2012.

[7] Nazim Beratli in personal correspondence.

[8] Ahmet Gazioglu Turks in Cyprus page 181. & table II page 21 of Halil Inalcik, Ottoman politics and administration in Cyprus after the conquest.

[9] Halil Inalcik page 22, table 3. Ottoman politics and administration in Cyprus after the conquest.

[10] Studies in History, International Journal of History. 2012. Page 136.

[11] Halil Inalcik page 22, table 3. Ottoman policy and administration in Cyprus after the conquest.

[12] Names and places of Cyprus lost in the depths of 2500 years of history, by Dr. Ata Atun.

[13] General Directorate of State Archives of the Republic of Turkey. 1831-3 Ottoman Population Archives. Archives of the National Estatales of the Republic of Turkey. 1831 Censo automano de 145. “Cyprus under Ottoman Administration, Population-Land Distribution”

[14] The first family records of Lurucina, by Ibrahim Tahsildar (Tahsildar was a tax collector who kept records of all the families of Lurucina.

[15] The Centuries-Long Struggle for Existence of the Raiders (Lurucina) Turks Por Hasan Yücelen ‘Mudaho’.

[16] Ruppert Gunnis. Historical Cyprus 1936. Pages 329-330.

[17] Lord Kitchener’s Maps. Section 10, drawn up in 1882 and published in 1885.

[18] Studies in History, International Journal of History 2012 Page 136.

[19] Excerpta Cypria 1908. Cyprian. Page 355.

[20] The Turks in Cyprus by Ahmet Gazioglu, 1990. Page 77.

[21] Extract from Cypria. 1908. Page 181.

[22] Palmieri 1905: col. 2462; Cirilli 1898: 14-15.

[23] George’s Hill. The Story of Cyprus page 305. 1952

[24] Excerpt from Cypria 1908. Page 181-184.

[25] The Turks in Cyprus by Ahmet Gazioglu, 1990. Page 74.

[26]The Turks in Cyprus by Ahmet Gazioglu, 1990. Pages 91-92.

0 Comments